Ethiopia › Forums › Ludicrous World › Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF)

-

AuthorPosts

-

30th November 2020 at 1:30 pm #338

Abiy Ahmed Ali lies

Speaking about Tigray refugees in Sudan, Abiy Ahmed Ali told MPs “There are no women and children [among them]. Those who are said to be refugees are only young [men]. Time will tell who are those youngsters.”

Nearly half of the refugees are children and women constitute a significant number of all registered adults. We saw and spoke to many of them in the refugee camps we visited in Sudan.

Ethiopia Autonomous Media

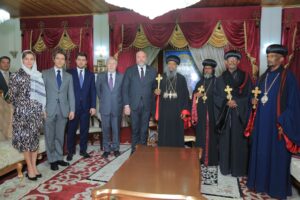

30th November 2020 at 4:01 pm #33930th November 2020 at 4:11 pm #340President Sahle-Work Zewde is on an official visit to Djibouti

President Sahle-Work Zewde is on an official visit to Djibouti where she served as Ethiopia’s ambassador for close to 10 years.

The President who arrived in Djibouti this morning held talks with President Ismail Omar Guelleh on bilateral and regional issues.

The President who arrived in Djibouti this morning held talks with President Ismail Omar Guelleh on bilateral and regional issues.Ethiopia Autonomous Media

30th November 2020 at 4:24 pm #341Ethiopian refugees

Ethiopian refugees wait in line for a meal at the Um Rakuba refugee camp, on the Sudan-Ethiopia border

International Committee of the Red Cross say hospitals & health facilities in Tigray state capital Mekelle are running low on medical supplies. Say Ayder Referral Hospital is low on sutures, antibiotics, food supplies painkillers and body bags for the deceased.

Let’s be honest! Just now the end of TPLF! Please stop and think again! What TPLF has done to Tigray people,27 yrs?How many Tigrians are suffering from deep poverty!Tigray people need change! Need peace and prosperity! Tigray people need to live with Amhara and Eritrean people!

Ethiopia Autonomous Media

12th December 2020 at 6:40 pm #494Hundreds of thousands of people are displaced as fighting continues

Hundreds of thousands of people are displaced as fighting continues between government forces and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front in northern Ethiopia, threatening the stability of a volatile region. Cameron Hudson, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center and former director for African affairs at the National Security Council joins to discuss the conflict and its impact.

Hari Sreenivasan:

For more on the continuing conflict in Ethiopia and the impact it is having on the region, I spoke with Cameron Hudson, a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center and former Director for African Affairs at the National Security Council during the George W. Bush administration.

Cameron, we’ve been reporting on the momentary kind of strife that’s been happening on a weekend by weekend basis, but if you could explain for us, put this in perspective, what is the conflict about?

Cameron Hudson:Well, the conflict is really about kind of ethnic federalism.

Ethiopia is made up of 10 different ethnic regions and a lot of autonomy has been devolved down to that regional level. And as part of Prime Minister Abiy’s kind of overall democratic reform process, he really sought to erase a lot of those ethnic differences in the country and promoted a kind of pan-Ethiopian nationalism, almost. And I think what you’re seeing here, certainly in the Tigray region, which is traditionally where the power center has been in the country, is a feeling that they have been sort of capsid in the political process in the country. And you’re seeing now a kind of more formalized agitation for a return to kind of ethnic federalism and the promotion of ethnic rights. And so, it is really part of a democratic reform process that Abiy has been undertaking, but which probably hasn’t had enough buy in from all of these ethnic minorities across the country.

Hari Sreenivasan:I mean, this is a person who won a Nobel Peace Prize. Yet here he is, part of a conflict that has displaced hundreds of thousands of people.

Cameron Hudson:The Nobel Prize was obviously for an international effort to heal wounds of the war with Eritrea, which took place in the late 1990s. What we’re seeing now, though, is Eritrea, as the partner in peace, may have now become the partner in war.

We have seen cooperation between Ethiopia and Eritrea and even the active involvement of the Eritrean forces in this conflict in Tigray. And so I think that with respect to the Nobel, people are asking whether it was premature. I think it was a kind of a hoped-for movement in a direction of peace. But what we’re seeing is his effort to make peace with Eritrea is not a reflection on his tactics domestically.

Hari Sreenivasan:What are the consequences for the countries surrounding this region as displaced people start to head for those borders?

Cameron Hudson:Well, it’s huge.

I mean, you cannot underestimate the, frankly, the beneficial role that Ethiopia has played in the region. It is the largest provider of peacekeeping forces on the continent of Africa, and it has played an essential role in conflicts in Somalia and Sudan in recent years. It is the largest provider of peacekeepers in the Somali conflict, which we as a US government have spent billions being a part of and trying to stabilize that country.

We’re on the precipice of seeing Ethiopian troops completely withdrawn from that theater in advance of of elections there. Obviously, they’ve also been a major peacemaker and mediator in conflicts in both Sudan, the revolution, the democratic revolution that’s been going on there and the civil conflict that took place in South Sudan just a few years ago.

So if we see Ethiopia move from the traditional role of peacemaker and mediator to a net exporter of instability, then you could see an entire region really, really destabilized going forward.

Hari Sreenivasan:Tell me a little bit about the humanitarian crisis that happens when all these people leave their homes.

Cameron Hudson:Well, right now, it’s really hard to assess the degree of the humanitarian crisis because the region has been so cut off to outside humanitarian assistance and even communications. So even though this week the U.N. reached an agreement with the Abiy government to allow humanitarian access into the region, we’ve seen that fighting up until today, up and through today, has really prevented those assessment missions from even getting eyes on the situation.

But we do know that even before this conflict started, this was an incredibly insecure region. As much as 20 percent of the population was food insecure, there were over a hundred thousand internally displaced — there are estimates now that there are a million internally displaced people.

We really only have access to about the 50,000 or so that have crossed the border in the last few weeks into Sudan. But when we know that there are pockets of of internally displaced that we are not able to access and the fears are growing, that those are populations that were surviving on international assistance, that international assistance has been cut off for the last month of fighting. And so we really don’t know what we’re going to find when we’re finally able to access those areas.

Hari Sreenivasan:If the fighting officially comes to an end, does that mean that the forces that are in opposition just literally head for the hills and fight from there?

Cameron Hudson:Well, that seems to be what’s happening right now. I mean, last weekend there was this very tense standoff around the regional Tigrayan capital of Mekelle, which was encircled essentially by federal government troops. The siege of Mekelle never happened because the Tigran leaders and have fled into the mountains surrounding the region.

I think we have to recall Ethiopia’s recent history. It fought a very long war against a communist Derg where the TPLF, the Tigrayan Party, essentially led a counterinsurgency campaign from the hills to overthrow this communist regime. And so I think there’s a great fear that they’re going to kind of return to their roots and not fight a conventional fight against federal government forces, but instead go to the mountains and try for a sort of asymmetrical warfare. And in that case, it might not be limited to the Tigray region. You could see conflict spilling over into other parts of the country, trying to draw in these other ethnic groups into the fight that they have started.

Hari Sreenivasan:Cameron Hudson, thanks so much for joining us.

Cameron Hudson:Thank you.

Ethiopia Autonomous Media

12th December 2020 at 6:50 pm #495Ethiopia returning thousands of refugees to Eritrea

In a development the United Nations has called “disturbing,” Ethiopia on Friday said it was returning thousands of refugees who ran from camps in its Tigray region as war swept through, putting them on buses back to the border area with Eritrea, the country from which the refugees originally fled.

The news came as the United States said it believes Eritrean troops are active in Ethiopia, something it called a “grave development”. A State Department spokesperson in an email cited credible reports and said “we urge that any such troops be withdrawn immediately”.

The UN refugee chief, Filippo Grandi, said that “over the last month, we have received an overwhelming number of disturbing reports of Eritrean refugees in Tigray being killed, abducted and forcibly returned to Eritrea. If confirmed, these actions would constitute a major violation of international law”. He said his agency has met with some refugees in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, and he again urged unhindered humanitarian access to Tigray.

Ethiopia said its recently completed military offensive against the now-fugitive Tigray regional government “was not a direct threat” to the 96,000 “misinformed” Eritrean refugees — even as aid groups said four staffers had been killed in the fighting, at least one in a refugee camp.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres this week said Ethiopian prime minister Abiy Ahmed, last year’s Nobel Peace Prize winner, “guaranteed to me that (Eritrean forces) have not entered Tigrayan territory”. But Tigray residents have asserted that gunfire came from the direction of Eritrea as the conflict began.

‘Alarming messages’

Eritrea, described by rights groups as one of the world’s most repressive countries, is a bitter enemy of the fugitive Tigray government.The UN’s refugee agency said it hadn’t been informed in advance of the Eritrean refugees’ return. “We received alarming messages from Eritreans living abroad and when we looked into them, ascertained that several hundred refugees had been put on buses this morning to be returned to the Tigray region,” it said.

Any forced return, it said, “would be absolutely unacceptable”.

Given the trauma that refugees say they witnessed in Tigray, they should be protected elsewhere, the agency said. It said the refugee camps have had no access to food or other supplies for more than a month.

The International Organisation for Migration said it was “extremely concerned” about the refugees’ “forced” return and denied it was involved, saying Ethiopia took over one of its transit centres in the capital, Addis Ababa, on December 3.

Aid groups say thousands of Eritrean refugees had fled to Addis Ababa and the Tigray capital, Mekele. Ethiopia said their “unregulated movement” makes it difficult to ensure their security.

Their camps are now stable and under “full control,” Ethiopia said, adding that food delivery there “is underway”.

But communication and transport links to Tigray remain so challenging that the International Rescue Committee said it was still trying to confirm details around the killing of a colleague in the Hitsats refugee camp in Shire town, the base of aid operations.

Separately, the Danish Refugee Council said three staffers who worked as guards at a project site were killed last month. It was not clear where, but the group also supports the Eritrean refugees.

“Sadly, due to the lack of communications and ongoing insecurity in the region, it has not yet been possible to reach their families,” the group said.

“Now, more than ever, it is a matter of urgency to cease all hostilities,” the European Union’s commissioner for crisis management, Janez Lenarcic, said while condemning the killings.

Food rations scarce

Tigray remains largely sealed off from the world five weeks after fighting erupted between Ethiopia’s government and the Tigray one following a months-long power struggle. The governments regard each other as illegitimate, the result of months of friction since Abiy took office in 2018 and sidelined the once-dominant Tigray People’s Liberation Front.Thousands of people are thought to have been killed in the fighting that began Nov. 4 and has threatened to destabilise the Horn of Africa.

Ethiopia rejects “interference” as fighting reportedly continues, while the UN has pleaded for neutral, unfettered access. “Food rations for displaced people in Tigray have run out,” the UN humanitarian office tweeted.

“Every day that we don’t have access is a day lost. Every day that we don’t have access is a day that increases the suffering of civilians,” UN spokesman Stephane Dujarric told reporters, and he referred questions to Ethiopia’s side.

Ethiopia says it is responsible for ensuring the security of aid efforts — though the conflict and related ethnic tensions have left many Tigrayans wary of government forces.

On Friday, Ethiopia said it had begun delivering aid to areas in Tigray under its control, including Shire and Mekele, a city of a half-million people.

“Suggestions that humanitarian assistance is impeded due to active military combat in several cities and surrounding areas within the Tigray region is untrue and undermines the critical work undertaken by the National Defence Forces to stabilise the region,” the prime minister’s office said, noting only “sporadic gunfire” remained.

Some 6 million people live in Tigray. About 1 million are now thought to be displaced. The impact on civilians has been “appalling,” the UN human rights chief said this week.

This week, Ethiopia said its forces shot at and briefly detained UN staffers conducting their first security assessment in Tigray, a crucial step in delivering aid. Ethiopia said they were trying to go where they weren’t allowed.

Meanwhile, nearly 50,000 Ethiopians have fled to Sudan and more are still arriving.

“The recent groups coming from areas deeper inside Tigray are arriving weak and exhausted, some reporting they spent two weeks on the run inside Ethiopia as they made their way to the border,” UN refugee spokesman Babar Baloch told reporters. “They have told us harrowing accounts of being stopped by armed groups and robbed of their possessions.”

Without access in Ethiopia, he said, “we are unable to verify these disturbing reports”.

Ethiopia Autonomous Media

12th December 2020 at 7:06 pm #496Ethiopia faces a rising debt to service

Ethiopia faces a rising debt to service, while major companies are pulling out of plans to locate there. Meanwhile the war rages on.

When Bangladeshi textile firm DBL set up shop in Ethiopia two years ago, the African nation was the garment industry’s bright new frontier, boasting abundant cheap labour and a government keen to woo companies with tax breaks and cheap loans.

When Bangladeshi textile firm DBL set up shop in Ethiopia two years ago, the African nation was the garment industry’s bright new frontier, boasting abundant cheap labour and a government keen to woo companies with tax breaks and cheap loans.Last month, as fighting raged in the northern Tigray region, DBL’s compound was rocked by an explosion that blasted out the factory’s windows, radically altering its business calculus.

“All we could do was to pray out loud,” said Adbul Waseq, an official at the company, which makes clothes mainly for Swedish fashion giant H&M and is one of at least three foreign garment makers to have suspended operations in Tigray.

“We could have died,” Waseq told the media.

For over a decade, Ethiopia has invested billions of dollars in infrastructure such as hydro-electric dams, railways, roads as well as industrial parks in an ambitious bid to transform the poor, mainly agrarian nation into a manufacturing powerhouse.

By 2017, it was the world’s fastest growing economy.

A year later, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed took office, pledging to loosen the state’s grip on an economy with over 100 million people and liberalise sectors such as telecoms, fuelling something akin to glasnost-era headiness among investors.

But for two years Ethiopia has been pummelled by challenges: ethnic clashes, floods, locust swarms and coronavirus lockdowns.

Now, fighting which erupted on Nov. 4 between the army and forces loyal to Tigray’s former ruling party, and fears it could signal a period of prolonged unrest, have served investors with a harsh reality check.

Any hesitation by investors could spell trouble as the country’s manufacturing export push isn’t yet generating enough foreign currency either to pay for all the country’s imports or keep pace with rising debt service costs. Even before the pandemic, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had warned that Ethiopia was at high risk of debt distress.

Abiy’s government said that, amid the crises it’s facing, Ethiopia was pushing ahead with reforms that will build the foundations for a modern economy.

“Despite the unprecedented shock from COVID and continued insecurity in different parts of the country, the Ethiopian economy showed remarkable resilience,” Mamo Mihretu, senior policy adviser in the prime minister’s office, told Reuters.

Ethiopia is a relatively small textiles producer with exports in 2016 of just $94 million compared with $29 billion for Vietnam and $253 billion for China in the same year, World Bank trade data showed. Its top exports are agricultural, such as coffee, tea, spices, oil seeds, plants and flowers.

But Ethiopia’s push into the textile industry over the past 10 years has been emblematic of its manufacturing ambitions.

As fighting neared Tigray’s regional capital, Mekelle, textile companies began shutting down and pulling out staff.

“It seemed that the conflict was getting closer to the city, and our worry was that we wouldn’t be able to leave,” Cristiano Frati, an electrician evacuated from a factory run by Italian hosiery chain Calzedonia, told an Italian newspaper.

Calzedonia said on November 13 it had suspended operations at the plant, which employs about 2,000 people, due to the conflict. It has declined to comment further.

DBL, meanwhile, has flown its foreign staff out of Ethiopia.

“Everything has become uncertain,” its managing director M.A. Jabbar said. “When will the war end?”

Another foreign company, Velocity Apparelz Companies – a supplier to H&M and Children’s Place – has also temporarily shut down, a company official told Reuters.

H&M said it was “very concerned” and was closely monitoring the situation.

“We have three suppliers in Tigray, and the production there has come to a halt,” the company told Reuters, emphasising that it would continue to source from Ethiopia where it has about 10 suppliers in total.

Indochine Apparel, a Chinese firm that supplies Levi Strauss & Co, said its operations in the Hawassa industrial park in the south of the country were unaffected.

Levi Strauss said it was monitoring the situation and confirmed there had been no impact on its supply chain so far.

Ethiopia’s apparel sector was struggling even before the fighting in Tigray because of the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. Some facilities did not survive the collapse in orders while others slashed wages or laid off staff.

The malaise has not been limited to the garment sector.

Even before the conflict, insurance companies underwriting political risk had stopped providing cover beyond Ethiopia’s northern Amhara region and the federal capital Addis Ababa, a risk consultant who advises corporate clients said.

“Ethiopia is not a pretty picture right now,” he said.

Like most sources contacted by Reuters, the consultant asked not to be named, fearing a backlash from government authorities.

Abiy’s efforts to ease a repressive political climate had already uncorked ethnic clashes before the war in Tigray. Violence in other parts of the country which intensified in 2019 had disrupted projects, notably in agriculture.

“The fighting started around the time we were going to start planting,” said the head of an agri-industry project that was forced to delay its investment last year.

Swedish furniture giant IKEA opened a purchasing office in Ethiopia last year. However, it closed it down in September after shelving plans to source from the country due to the political and social situation, COVID-19 and changes to the cotton market in Africa, the company told Reuters.

Meanwhile, Coca-Cola Beverages Africa, a bottling partner of the Coca-Cola Company, told Reuters that the fighting in Tigray, which accounts for about 20 per cent of its sales volumes in Ethiopia, had halted business there.

That comes on the heels of delays in the construction of two new bottling plants – part of a $300 million five-year investment plan announced last year – due to the pandemic and an excise tax increase.

With the fall of Mekelle at the end of last month, Abiy declared victory over Tigray’s former ruling party (TPLF).

“The swift, decisive, and determined completion of the active phase of the military operation means any lingering concerns about political uncertainty by the investment community will be effectively settled,” Abiy’s adviser Mamo said.

The TPLF has vowed to fight on.

For the government, there is little margin for error. Ethiopia’s external debt has ballooned five-fold over the past decade as the government borrowed heavily – notably from China – to pay for infrastructure and industrial parks.

Foreign direct investment inflows, meanwhile, have declined steadily since a 2016 peak of more than $4 billion, slipping to about $500 million for the first quarter of this fiscal year.

Inflation is hovering around 20%.

“There are very few ways out of this. They aren’t going to get more money from the IMF. They can’t go to the markets. Their best bet is a global economic recovery next year,” said Menzi Ndhlovu, senior country and political risk analyst at Signal Risk, an Africa-focused business consultancy.

Still, Ethiopia passed a landmark investment law earlier this year and implemented currency reforms.

And the government is pushing ahead its plans to open up the telecommunications sector. It opened tendering for two new telecoms licences at the end of November and plans to sell off a minority stake in state-owned Ethio Telecom.

Sources following the process, which should provide the beleaguered economy with a hefty injection of dollars, said interested companies were not deterred by the current unrest.

But for now, Ethiopia’s grand manufacturing dreams have been dealt a setback.

“Who will go there in this situation?” asked DBL’s Waseq, who has returned to Bangladesh. “No one.”

Ethiopia Autonomous Media

13th December 2020 at 12:25 am #497The U.N. under-secretary-general for humanitarian affairs

Mark Lowcock is the U.N. under-secretary-general for humanitarian affairs.

I was first in northern Ethiopia in the mid-’80s in the wake of the horrific famine that took the lives of a million people. In the 35 years since then, Ethiopia’s story has been one of remarkable progress. Children in school and jobs created. Roads, railways, factories and power stations built. Addis Ababa became one of the leading African cities; Ethiopia a bulwark of relative stability in the region.

What’s tragic about the current conflict is the danger of all that progress being lost.As I write, the conflict in and around Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region is well into its fifth week, with hundreds of people reportedly killed, tens of thousands displaced and millions enduring day after day without food, water and power.

As Michelle Bachelet, the U.N. high commissioner for human rights, has said, we have corroborated evidence of gross human rights violations and abuses and serious violations of international humanitarian law, including indiscriminate attacks that have resulted in civilian casualties, looting, abductions and sexual violence against women and girls, as well as reports of forced recruitment of Tigrayan youth to fight against their own communities.

We are also receiving disturbing reports of Tigrayans being identified and singled out in their jobs in other parts of the country.

The Red Cross has reported that the main hospital in Mekelle, the capital of Tigray, has no supplies, fuel or running water. Doctors and nurses have had to suspend intensive care services and are struggling with routine care, such as delivering babies or providing dialysis treatment. We have also received reports of women dying during childbirth — preventable deaths — due to the lack of adequate services and supplies.

The conflict is escalating and threatens to spiral out of control. There are reports that militias from non-Tigrayan backgrounds, armed with competing agendas, are now involved in the fighting. The last thing needed is external agitators pouring fuel on the fire.

So what can be done?

The United Nations and other humanitarian agencies need immediate and unfettered access so we can scale up urgently needed assistance and protection for vulnerable civilians, and get supplies to our teams on the ground. We’re talking to the federal government of Ethiopia and others on a daily basis to grant safe passage to humanitarian workers and supplies to the affected region, in line with the globally agreed principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and operational independence.

Access needs to go hand in hand with security for aid workers. Humanitarian workers must be able to deliver aid without fear of attack. Tragically, we have received reports of aid workers, who courageously stayed behind to support their communities, being killed during the course of this conflict.

What’s happening in Tigray right now is fundamentally a political problem. It won’t be resolved by violence. In the meantime, it is civilians who are bearing the brunt of the conflict. This must stop.

There’s a lot at stake. People should not be sanguine about the risks. Chaos in the Horn of Africa is in no one’s interest.

The United Nations strongly urges all parties to the Tigray crisis to seize the initiative led by the chairperson of the African Union, President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa, to facilitate peaceful solutions and de-escalate tensions.

Conflicts like this are hard to stop once they get out of control — the lives they extinguish cannot be brought back, and the grievances they create are long-lasting.

Ethiopia Autonomous Media

15th December 2020 at 10:56 pm #516Accounts of civilian casualties in Tigray region

Accounts of civilian casualties have been emerging from Ethiopia’s war-torn Tigray region. Humanitarian organizations are increasingly worried about living conditions for the survivors of the conflict.

There is little information about the situation in Shire, a town in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region.

Telecommunications are shut down. Organizations can only speculate about the extent of casualties and material damage after clashes between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and federal forces.

Ethiopian refugees who fled to Sudan from Tigray wait in line to receive food aid

But when Semira’s* relative was able to escape the town thanks to his Saudi Arabian ID, he brought bad news with him. Five of their family members died after being shot.“It had been a long time since I last saw my father cry,” said Semira, who is half Tigrayan, half Eritrean.

“The people that I know, they hate the TPLF. But now they want the TPLF to win. They want them to take over the power. Even people who had hope in [Ethiopia’s prime minister, Abiy Ahmed]. For now, we only heard about five people, we don’t know about the others. There are young people of whom we don’t know where they are, they are fighting.”

Unfolding humanitarian crisis

Fighting between the federal government and the TPLF started early November.

The Tigray region of Ethiopia has been almost entirely shut off from the rest of the world since fighting broke out. Communications were partially restored in the Western part of the region a few weeks ago, and in and around Tigray’s capital, Mekele, on Sunday.

This came as a relief for families who were able to reconnect after almost six weeks of silence and uncertainty.

But for the rest — the North and Central areas — questions linger.

Aid access

The UN Security Council on Monday held an informal meeting on the humanitarian situation in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, where the majority of humanitarian organizations are not allowed to enter.A humanitarian crisis is unfolding on such a scale that organizations are afraid of what they will find once allowed in. Reports about civilian casualties are becoming more frequent, contradicting claims by both the TPLF and the government that no harm has been caused to civilians.

The UN’s humanitarian body is preparing for an estimated 1.1 million people who are in need of humanitarian assistance, in addition to the 600,000 people who were already depending on food aid. Hundreds of thousands are believed to be internally displaced and food rations have run out.

So far, almost no humanitarian access has been granted despite a November agreement between the Ethiopian government and UN agencies allowing aid into government-controlled areas of Tigray.

Wounded and sick

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) was one of the only humanitarian organizations to finally be allowed into the region’s capital, where the prime minister paid a visit on Sunday.“We have sent seven trucks to Mekele to transport medical items and relief supplies,” explained Zewdu Ayalew, head of communications for the ICRC delegation in Ethiopia.

“The wounded and the sick people were not in a position to get proper medication and the hospital was forced to suspend services in its intensive care unit and other routine medical services.”

Power has now been restored and Mekele’s health facilities are able to slowly resume their services.

But the ICRC has been an exception so far.

Complex environment

Ethiopia “doesn’t need a babysitter,” Redwan Hussein, spokesman for the emergency task force, said in a press conference with regards to humanitarian access. He accused the UN of not cooperating after the agreement was signed on November 29.Early in December, four UN staff members were shot at by federal forces during an assessment visit. The government said this occurred after the staff broke through two checkpoints leading up to a refugee camp.

This incident “highlights the complex situation we have now in Tigray and the need for us to have safe, unconditional and free access to the area to make sure that we can assist people there,” according to Saviano Abreu, a spokesperson for the UN’s humanitarian coordination office (OCHA).

Negotiations are still underway between the UN, the government and other humanitarian actors, but it’s unlikely that unfettered access will be granted in the near future.

“This agreement says the UN, and other organizations who are taking care of refugees, have unlimited access to this region,” explained Chris Melzer, the UNHCR spokesperson in Ethiopia.

“We probably had different definitions about unlimited access.”

In reality, the agreement granted access in areas controlled by the federal army, and “only when the government allows that every single step. Ethiopia is a host country, we are guests here and of course we will respect the law of Ethiopia. But we really hope that the government of Ethiopia also sees the need to help these people in the Tigray region,” Chris Melzer stressed.

Impatience is growing among humanitarian organizations, which are increasingly frustrated at the impossibility of carrying out their missions.

Internally displaced persons are of particular concern. They are likely to be scattered around rural areas after fleeing the fighting and could therefore be very difficult to reach.

Some NGOs fear food supplies might become stranded in main towns, such as Mekele or Shire, without access away from the main roads.

“People impacted by conflict must be assisted without distinction of any kind, other than the urgency of their needs,” OCHA’s Saviano Abreu insisted.

The case of Eritrean refugees

Concern is also growing for refugee populations in Tigray. The region is home to about 96,000 Eritrean refugees, who are heavily dependent on aid and could be a target in the conflict, where, according to several sources, Eritrean troops have taken part in hostilities. The Ethiopian government has repeatedly denied these claims.So far, the UNHCR has not been able to provide help to the four refugee camps in the region. Delivery of food and other items, which usually take place every four weeks, stopped early November. Camps have been left without supplies for over one week.

Hundreds of Eritrean refugees have fled camps in the region and were able to escape to Addis Ababa or Gondar. But on Friday the government said it is “safely returning refugees to their respective camps,” providing assurance that food aid was on its way.

“We are talking about families, about elderly people, about children who were born just weeks ago, months ago. We are concerned the situation is not really suitable for refugees there. Refugees fled this region for good reasons,” said Chris Melzer.

“On the other hand as soon as the government thinks the situation is safe now for the refugees, we think it must also be safe enough for the refugee helpers, and that’s why we think that very soon we can go back to the refugee camps.”

Ensuring safety for humanitarian staff will be no easy task. It’s unclear under what circumstances employees of the Danish Refugee Council and the International Rescue Committee were killed in November, and fighting is still being reported in some areas.

There are also fears of ethnic profiling — Tigrayan humanitarian workers have received repeated threats — but non-Tigrayans could expose themselves to other risks.

Organizations are nonetheless determined to do their best at providing assistance for thousands who are waiting in despair.

“My family is lucky, they had somewhere to go, they had someone to be with. But what about those who don’t have anything?” Semira asked.

Despite the fear, she decided to speak up, especially on social media. She worries about the fate of the region, especially Shire, her father’s birthplace.

“Why can’t they [humanitarians] go there? This is the question. I feel like they burned this city to the ground,” she whispered, in tears.

Ethiopia Autonomous Media

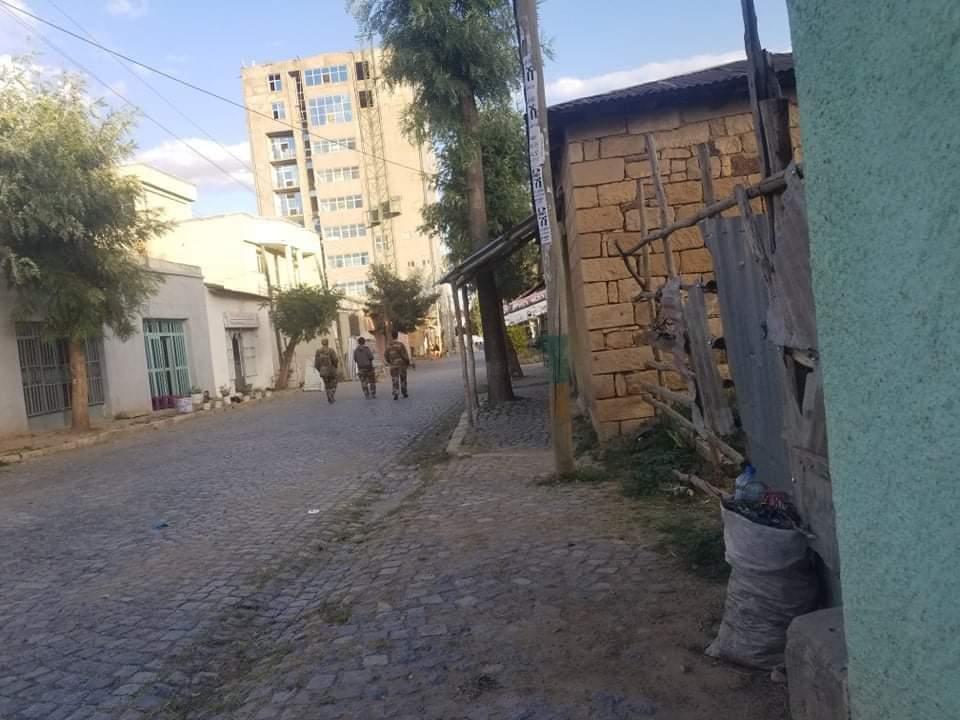

31st December 2020 at 7:54 pm #592HEALTH CENTRES IN TIGRAY ARE LOOTED AND VANDALIZED BY ERITREAN TROOPS

Every health centres in Tigray are looted and vandalized by the savage Eritrean troops. Drugs, medical devices, and equipment’s emptied from all health facilities in Tigray by Eritrean armies, leaving the rest in ruins.

This is one reason why dictator Abiy Ahmed Ali is blocking UN delegates to enter to the region.

This is one reason why dictator Abiy Ahmed Ali is blocking UN delegates to enter to the region.

Eritrean soldiers in Adigrat, Tigray. They did not even change their camouflage to pretend to be Ethiopian soldiers.

Eritrean soldiers in Adigrat, Tigray. They did not even change their camouflage to pretend to be Ethiopian soldiers. From Wukro to Adigrat pharmacies are looted & destroyed by Eritrean & Ethiopian troops. isn’t hard to imagine what they did to the people who work there. Eritrean soldiers are still in Tigray killing & terrorising civilians. It has to stop! the world must ACT!

From Wukro to Adigrat pharmacies are looted & destroyed by Eritrean & Ethiopian troops. isn’t hard to imagine what they did to the people who work there. Eritrean soldiers are still in Tigray killing & terrorising civilians. It has to stop! the world must ACT! Ethiopia Autonomous Media

31st December 2020 at 8:27 pm #593Factories in Tigray Looted and destroyed by Eritrean Soldiers

Almeda textile factory was one of the leading textile manufacturers in Tigray which offers employment opportunities for more than 300 people. The factory, is now completely destroyed and looted by the Eritrean soldiers.

One of the main reasons why the vindictive Isaias Afwerki got involved in the genocidal War On Tigray at the invitation of Abiy Ahmed Ali is to destroy all of Tigray’s basic infrastructures and carry both private and governmental looted Tigrayan properties to Eritrea.

One of the main reasons why the vindictive Isaias Afwerki got involved in the genocidal War On Tigray at the invitation of Abiy Ahmed Ali is to destroy all of Tigray’s basic infrastructures and carry both private and governmental looted Tigrayan properties to Eritrea.Let’s not forget the psychological impact of the progress Tigray made in the last 30 years on the jealous and fragile, Isaias, while his dictatorship couldn’t even maintain what the Italians built in Eritrea. Shame!

Ethiopia Autonomous Media

31st December 2020 at 8:59 pm #59631st December 2020 at 9:14 pm #597assault on Tigray region after a deadly Tigrayan attack

On Nov. 4, Ethiopian federal forces began an assault on Tigray region after a deadly Tigrayan attack and takeover of federal military units in the region. By November’s end, the army had entered the Tigrayan capital, Mekelle.

Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) leaders abandoned the city, claiming they wished to spare civilians. Much remains unclear, given a media blackout. But the violence has likely killed thousands of people, including many civilians; displaced more than a million internally; and led some 50,000 to flee to Sudan.

Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) leaders abandoned the city, claiming they wished to spare civilians. Much remains unclear, given a media blackout. But the violence has likely killed thousands of people, including many civilians; displaced more than a million internally; and led some 50,000 to flee to Sudan.

The Tigray crisis’s roots stretch back years. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed came to power in 2018 after protests largely driven by long-simmering anger at the then-ruling coalition, which had been in power since 1991 and which the TPLF dominated. Abiy’s tenure, which began with significant efforts at reforming a repressive governance system, has been marked by a loss of influence for Tigrayan leaders, who complain of being scapegoated for previous abuses and warily eye his rapprochement with the TPLF’s old foe, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki. Abiy’s allies accuse TPLF elites of seeking to maintain a disproportionate share of power, obstructing reform, and stoking trouble through violence.

TPLF’s old foe, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki. Abiy’s allies accuse TPLF elites of seeking to maintain a disproportionate share of power, obstructing reform, and stoking trouble through violence.The Tigray dispute is Ethiopia’s most bitter, but there are wider fault lines.

The Tigray dispute is Ethiopia’s most bitter, but there are wider fault lines.

Powerful regions are at loggerheads while supporters of Ethiopia’s ethnic federalist system (which devolves power to ethnically defined regions and that the TPLF was instrumental in designing) are battling that system’s opponents, who believe it entrenches ethnic identity and fosters division. While many Ethiopians blame the TPLF for years of oppressive rule, the Tigrayan party is not alone in fearing that Abiy aims to do away with the system in a quest to centralize authority. Notably, Abiy’s critics in the restive Oromia region—Ethiopia’s most populous—share that view, despite Abiy’s own Oromo heritage.

The question now is what comes next. Federal forces advanced and took control of Mekelle and other cities relatively quickly. Addis Ababa hopes that what it calls its continuing “law enforcement operation” will defeat the remaining rebels. It rejects talks with TPLF leaders; allowing impunity for outlaws who attack the military and violate the constitution would reward treason, Abiy’s allies say. The central government is now appointing an interim regional government, has issued arrest warrants for 167 Tigrayan officials and military officers, and appears to hope to persuade Tigrayans to abandon their erstwhile rulers. Yet the TPLF has a strong grassroots network.

There are disturbing signs. Reports suggest purges of Tigrayans from the army and their mistreatment elsewhere in the country. Militias from Amhara region, which borders Tigray, have seized disputed territory held for the past three decades by Tigrayans. The TPLF launched missiles at Eritrea, and Eritrean forces have almost certainly been involved in the anti-TPLF offensive. All this will fuel Tigrayan grievances and separatist sentiment.

If the federal government invests heavily in Tigray, works with the local civil service as it is rather than emptying it of the TPLF rank and file, stops the harassment of Tigrayans elsewhere, and runs disputed areas rather than leaving them to Amhara administrators, there might be some hope of peace. It would be critical then to move toward a national dialogue to heal the country’s deep divisions in Tigray and beyond. Absent that, the outlook is gloomy for a transition that inspired so much hope only a year ago.

Ethiopia Autonomous Media

31st December 2020 at 9:42 pm #598the conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region

The terrible toll of the conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region is coming into sharper focus. The human costs continue to mount; the United Nations estimates that 1.3 million people need emergency assistance as a result of the conflict, and over 50,000 people have fled to neighbouring Sudan. Eritrean refugees that had fled to Ethiopia have reportedly been attacked, in some cases forcibly repatriated.

UN agencies remain unable to access some areas with humanitarian relief. And despite the federal government’s assertion that the military operation ended in late November, some fighting clearly continues. The overall number of civilians killed remains unknown. The toll on regional stability will only become apparent over time, but it is already clear that Sudan’s fragile transition is suffering new perils as a result of the conflict in Ethiopia.

Prime Minister of Ethiopia Abiy Ahmed Ali at news conference after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, Norway December 11, 2019.

Prime Minister of Ethiopia Abiy Ahmed Ali at news conference after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, Norway December 11, 2019.

By Michelle Gavin

Prime Minister Abiy’s credibility is also among the losses. His claims in late November that not a single civilian was killed in the military assault on Tigray were contradicted by desperate testimonials that emerged despite the state’s attempt to impose a total communications blackout across the region. Ample, alarming evidence belies Abiy’s repeated denials of the involvement of Eritrean forces in Ethiopian territory. Journalists are being beaten and harassed, presumably for reporting the truth and sullying the rosy rhetoric from the leadership in Addis Ababa.

This loss of credibility may seem insignificant compared with the numbers killed, wounded, and displaced, but it is grave nonetheless. Ethiopia had long played an important stabilizing role in the region, and it had been emerging as a leading voice on behalf of the continent as a whole in important global discussions. Around the world, leaders embraced the vision of a stable, prosperous, inclusive, and accountable Ethiopia—a state strong enough to stand up for African interests and for shared global norms. But now the international community has reason to doubt the veracity of Abiy’s words and to second-guess his intentions—hardly a solid basis for fruitful partnerships. The cost, calculated in missed opportunities, could be staggering.

Ethiopia Autonomous Media

31st December 2020 at 10:31 pm #599access to Ethiopia’s crisis-ravaged Tigray region

With communication and access to Ethiopia’s crisis-ravaged Tigray region cut off, humanitarian agencies are having difficulty responding to those in need there and in refugee camps in neighbouring Sudan — among them pregnant women, vulnerable groups and newly born babies.

Thousands of Ethiopians have fled Tigray, Ethiopia’s northernmost region on the border with Eritrea, as national government forces have sought to reassert federal control over the area. Many are arriving in western neighbour Sudan without even the most basic necessities, say aid agency officials.

The bigger impact has been on fleeing women, who also face heightened risk of sexual violence and abuse as they journey. It has been worse for those pregnant or those who have just given birth.

The United Nations Population Fund estimated in late November that more than 700 of some 7,500 women refugees arriving in Sudan from Tigray were pregnant.

Other women and girls have just survived gender-based violence and are in need of specialist health care, which is in short supply. As the numbers tick up, so does the desperation and vulnerability of even more Ethiopian women from Tigray.

A 52-year-old Ethiopian refugee who recently arrived at a Sudan refugee camp after fleeing Tigray said there has not been sufficient aid from responders and humanitarian agencies to assist everyone in need. As a result of the shortages of relief material, only the fittest are able to rush to collect food when aid parcels are delivered.

Speaking through a humanitarian worker with the nongovernmental organization CARE International, the woman, from the city of Humera, said: “Nursing mothers and children are not getting help because the youth push them out of the way during distributions.”

Pope Francis has joined those calling for peace to prevail in Tigray and for the conflict to come to an end. In a Nov. 27 appeal, he noted that hundreds of civilians have died and tens of thousands have been forced to flee.

Tigray’s government is run by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which has come into tension with Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s government over the past year because of a scheme to reorganize the country’s political parties.

The TPLF has also claimed that Ahmed’s plan to postpone all elections in the country until 2021 because of the pandemic is illegitimate, and pushed ahead with its own regional elections last September.

The conflict escalated into violence Nov. 4, when the TPLF bombed the northern command office of the Ethiopian National Défense Force. National forces then launched military assaults on the TPLF in response, before claiming to have regained control of the Tigrayan capital, Mekelle, Nov. 28.

While more than 50,000 people have been displaced from Tigray, thousands of others have remained trapped inside the region. They face hunger and disease and are shut out from the rest of the world, as the federal government has shut down all communications infrastructure and closed the regional borders.

Aid and much-needed health services are beyond their reach. And fleeing into Sudan is increasingly being seen as a better option, despite the risks and dangers that lurk at every turn of that journey.

A 34-year-old refugee from Tigray who had just arrived in Sudan said pregnant women were among those pushing and shoving to access assistance from aid agencies.

“There are elderly people, mothers and pregnant women who came here to receive items. But there is no proper line and people are just pushing for themselves,” said the refugee, who asked not to be named.Currently, access to refugee camps is limited in the Tigray region. Hence, it is difficult to provide information on how are we responding to the humanitarian crisis. … Once we are provided access, then we will be able to continue our assistance.”

International humanitarian organizations such as Human Rights Watch fear that there are unreported abuses taking place within Tigray. The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees has already made an appeal for $147 million to support as many as 100,000 Ethiopians who are expected to flee into Sudan.

There are fears though, that the impact of the conflict on the humanitarian situation will be prolonged and that it could lead to further food insecurity and health issues beyond the crisis. Humanitarian efforts in Ethiopia have already been stretched because of the coronavirus pandemic.

The conflict will have a long-term impact on the humanitarian situation in the region as agricultural and economic activities are interrupted, and people will depend on humanitarian assistance for survival and for their livelihoods in the coming months.

The main hospital in Mekelle Tigray is paralyzed. No supplies, no fuel, no running water. Doctors & nurses have suspended intensive care services and are struggling to do routine care like delivering babies or providing dialysis treatment.

Ethiopia Autonomous Media

-

AuthorPosts

You must be logged in to reply to this topic.

The President who arrived in Djibouti this morning held talks with President Ismail Omar Guelleh on bilateral and regional issues.

The President who arrived in Djibouti this morning held talks with President Ismail Omar Guelleh on bilateral and regional issues.

This is one reason why dictator Abiy Ahmed Ali is blocking UN delegates to enter to the region.

This is one reason why dictator Abiy Ahmed Ali is blocking UN delegates to enter to the region.

Eritrean soldiers in Adigrat, Tigray. They did not even change their camouflage to pretend to be Ethiopian soldiers.

Eritrean soldiers in Adigrat, Tigray. They did not even change their camouflage to pretend to be Ethiopian soldiers.

One of the main reasons why the vindictive Isaias Afwerki got involved in the genocidal War On Tigray at the invitation of Abiy Ahmed Ali is to destroy all of Tigray’s basic infrastructures and carry both private and governmental looted Tigrayan properties to Eritrea.

One of the main reasons why the vindictive Isaias Afwerki got involved in the genocidal War On Tigray at the invitation of Abiy Ahmed Ali is to destroy all of Tigray’s basic infrastructures and carry both private and governmental looted Tigrayan properties to Eritrea.

Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) leaders abandoned the city, claiming they wished to spare civilians. Much remains unclear, given a media blackout. But the violence has likely killed thousands of people, including many civilians; displaced more than a million internally; and led some 50,000 to flee to Sudan.

Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) leaders abandoned the city, claiming they wished to spare civilians. Much remains unclear, given a media blackout. But the violence has likely killed thousands of people, including many civilians; displaced more than a million internally; and led some 50,000 to flee to Sudan.

TPLF’s old foe, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki. Abiy’s allies accuse TPLF elites of seeking to maintain a disproportionate share of power, obstructing reform, and stoking trouble through violence.

TPLF’s old foe, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki. Abiy’s allies accuse TPLF elites of seeking to maintain a disproportionate share of power, obstructing reform, and stoking trouble through violence.